Nutgall or iron tannin inks are made from gallic acids and ferrous sulphate, or green vitriol. When mixed together these chemicals form a substance which is virtually colorless, but which darkens when it is exposed to air. Once the ink comes into contact with paper it reacts with the paper fibres, forming a black iron compound in the fibres, which will last as long as the paper survives. Unfortunately, an almost colorless liquid is not much use as a writing material so an indigo or water-soluble blue aniline dye is added. As the ink writes the colour is blue, but with time the blue fades leaving a predominant black, which results from the oxidation of the ferrous tannate and gallate. Blue black ink describes the inks which write blue but become black. Because of the permanent nature of nutgall ink they are used for recording official documents.

The chemical iron tannim ink can form quite naturally, in Algeria there is a River of naturally occurring ink. Two tributaries join and one of the streams runs through iron enriched soil, and the water has absorbed the iron content. The other stream comes from a peat swamp and has tannin in it. When the two streams joined, there is a chemical reaction between the tannic acid, the iron and the oxygen in the water, which causes black ferric tannate, or ink to form.

The nutgalls are abnormal growths of the oak tree, the Quercus infectoria, which is abundant in the Middle East. They yield Aleppo galls which make the most suitable tannic acid for the manufacture of inks. Tannic and gallic acids in solution gradually turn a light brown when exposed to air, before they react with the ferrous sulphate to develop black. It takes time for the black precipitate to form and to prevent this occurring while the ink is still in the ink well sulphuric or hydrochloric acid is added to the ferrous sulphate which prevents this. The acid makes it more soluble which means that it penetrates the fibres of the paper and prevents the ink from clogging the pen.

Dickens and Warren’s Blacking Factory

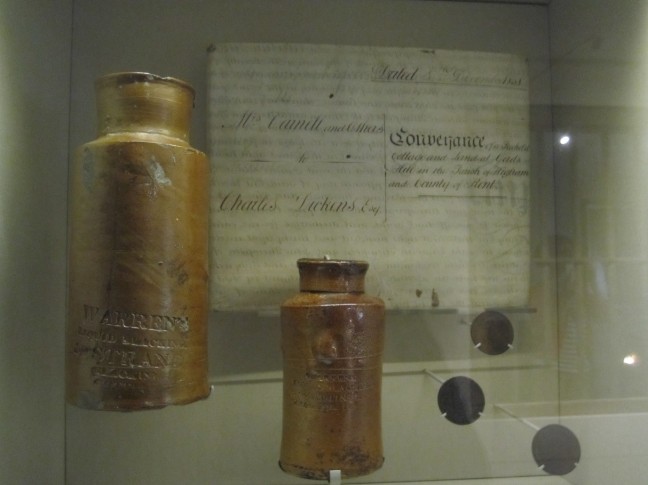

Bottles from Warren’s Blacking Factory where Charles Dickens worked in 1924. Held at the Charles Dickens Museum, London.

Bottles from Warren’s Blacking Factory where Charles Dickens worked in 1924. Held at the Charles Dickens Museum, London.

Charles Dickens and the Blacking Factory

Above are two bottles from Warren’s Blacking Factory where Charles Dickens worked in 1924, aged twelve, after his parents fell into debt. Charles’ job at the factory was to cover the bottles of paste-blacking and to make the bottle look smart with paper and labels so that they could be sold in apothecaries. For this he earned six shillings a week in wages and worked six days a week from 8am to 8pm. [1] This experience of working and independence was a significant period in Charles life, and later dwelt on this time with horror and indignation. During Charles Dickens childhood, his family got progressively poorer and by 1922 his father could no longer afford to send him to school despite already showing high levels of creativity and intelligence. After years of financial struggles, John Dickens was arrested for debt in 1924 where he was first held at a sponging house before being taken to the Marshalsea debtor’s prison in Southwark. At twelve years old, Charles became the man of the family and was sent to pawn the family’s possessions and furniture which lead to the family having to camp out in two bare rooms during cold weather. These experiences of debt, prison, pawnbrokers and living in cold rooms on what could be borrowed or begged deeply affected Dickens and were used in his novels. [2]

Charles was against being put to work at the blacking factory and resented his parents indifference to this; later reflecting in his life that, “my mother and father were quite satisfied. They could hardly have been more so, if I had been twenty years of age, distinguished at a grammar school, and going to Cambridge.” Charles’ job at Warren’s was incredibly light in comparison to other jobs they were in the factory as he could sit down to cover and label the pots. He was also given lessons during his lunch hour to keep up his education and made a friend called Bob Fagin, whose name he later used for one of his most famous villains. However, due to the hours he worked, Charles could not live with his family at the Marshalsea and had to board in a house in Camden. It is perhaps this separation from his family that affected Charles more than the factory work itself. Having to walk from Camden to the factory at Hungerford, next to the Thames, Charles witnessed a great many things in London and it is these that inspired moments and characters in his novels. Often at the centre of his novels is the figure of a lost, helpless or persecuted child; such as Oliver Twist, Little Nell, David, Paul Dombey and Pip. [3]

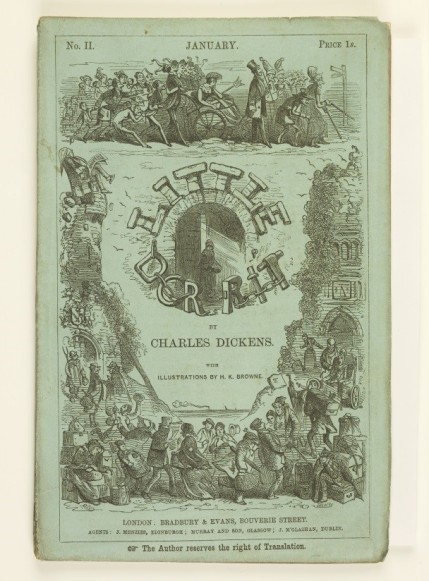

Little Dorrit tells the story of Amy (known as ‘Little Dorrit’) who grows up in the Marshalsea prison due to her father debts. (Copyright: V&A Images)

Victorian Children at Work: A Loss of Childhood?

Both Charles Dickens personal experience of working life and characterisation of working children in his novels and stories can be used by historians studying child labour in post-industrialised London and the family situations that lead children to go into work later in their childhood. Family relationships and structure was significant in the conditioning of children going to work. Jane Humphries has suggested three areas of research into family relationships; economic circumstances of the families, altruism (love of the parents) and the authority figure in the family who made decisions on children going to work. [4] Peter Kirby argues in Child Labour in Britain that the stimulus for child labour was family poverty, and that child labour only declined when poverty eased in the middle of the nineteenth century. [5] In general, historians now recognise that fathers and mothers were caring but the relationships between children and parents were powerfully gendered. This implicated both family life and family economy. But how did work at a young age affect a child in later life and their reflections on their own childhood?

Some local studies have found that working children found their contribution to the family economy vital and empowering. However, this was not felt by Dickens who remained deeply scarred by his experiences throughout his life. But perhaps this is because Dickens had to live independently at age twelve as he could not live with the rest of his family at the Marshalsea prison. He had to depend on himself to get to and from work across London and make all his meals. It is also said that Charles could not walk the route from Camden to the river in his adult life as it would often reduce him to tears. Furthermore, George Lander’s analysis the ‘dark side’ of Dicken’s work illuminates his resentment of his parents and how he found his work experience shaming and traumatic as he felt he lost his right to an education. But Dicken’s experience did allow him to write realistic stories of lost and helpless children. The prevention and restriction of child work would impact many families income but would protect the period of childhood.

Children became more visible during and after the Industrial Revolution and often worked as they could make a significant contribution to their family’s economy. Just like in Charles Dickens case, most children probably worked when they needed to if there was no father or if their parent’s wages were low. It is hard to judge how this affected children’s experience of childhood as some studies have found a pride in children who contributed to their family’s income, whereas others have found that children, such as Charles Dickens, found the experience traumatic and damaging. This does not mean to say that children who went into work didn’t have a childhood, it just means that the period they would recognise as childhood ended at an earlier age than if they had not gone into work.

Footnotes

[1] John Forster, The Life of Charles Dickens, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1872-1874) 24.

[2] Claire Tomalin, Charles Dickens: A Life, (London: Penguin Group, 2011) 22-23.

[3] victorianweb.org (accessed: 7/11/2016)

[4] Jane Humphries, Childhood and Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010) 125.

[5] Peter Kirby, Child Labour in Britain, 1750-1870, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003)

Further Reading

Bennett, Alan. A Working Life: Child Labour Through the Nineteenth Century. Poole: Waterfront, 1991.

Hopkins, Eric. Childhood Transformed: Working Class Children in Nineteenth Century England. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994.

Horseman, Alan. “Introduction” in Dombey and Son. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974.

Lavalette, Michael. A Thing of The Past? Child Labour in Britain in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1999.

Slater, Michael. Dickens and Women. Bungay: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd, 1983.

Electronic Resources

http://www.emmajolly.co.uk/blog/tag/charles-dickens-2/

https://lisawallerrogers.com/tag/warrens-blacking-factory/

http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/dickens/dickensbio3.html

One thought on “Dickens and Warren’s Blacking Factory”

Leave a Reply

Your very informative article has Chas. Dickens working at the blacking factory in ‘1924‘. Perhaps you meant ‘1824’?

Like