Rivelin tunnel

Construction of the tunnel began in 1903 and was completed in 1909. It was built to use the plentiful supplies of the River Derwent as compensation water for the River Rivelin rather than draining the more valuable waters of Redmires Reservoirs. The tunnel is 4.5 miles (7.2 km) long, 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m) high and 6 ft (1.8 m) wide, it has a fall towards Rivelin of 1 in 3,600 which is 6 ft 7in (2.0m) over its entire length. The tunnel takes water which has come through a drain hole in the south east corner of Ladybower Reservoir and delivers it into the Lower Rivelin Reservoir with the tunnel emerging into a grass covered underground tank on the south bank at a point next to where the Wyming Brook enters the Lower reservoir. The tunnel cost £135,151, which was £13,000 under budget.[4]

The ground tunnelled through consisted of millstone grit and hard shale

interspersed with bands of rock. with the exception of the Severn

Tunnel, which is only 12 yards longer, it is the longest tunnel in

England, and certainly the longest in Great Britain for Waterworks

purposes.

During the construction enormous quantities of water were encountered and even today about 5% more water exits the tunnel than enters it.

Image information

| |||||||||||||||||

(Тоннель ривелин)

After the tunnel had been completed Mr Mappin Wilson of Sheffield, who had shot the moor under which the tunnel passed, sued the Water Board for compensation because, he said,"his grouse had less to drink, due to water filtering down into the tunnel from the moor above". His claim was for £5,000 and £3,600 for loss of water. A surveyor from Huddersfield was brought in and he put the total loss at £4,000. The Sheffield engineer to the Water Board said that as there had been no surface disturbance the draining away of water suggestion was ludicrous and he put nominal damages at £100. As no agreement could be reached, the case went before Colonel Welland at the Surveyors Institute, Westminster, and the final award reached was for £1,500. Wilsons gamekeeper a Mr Dolman, later said that the tunnel was the best thing that ever happened, because the moor became drier and better for grouse and breeding purposes, W/E. { Moorland Heritage by James S Byford}Most Sheffielders are aware of the Totley Tunnel that carries the railway line out through the Hope Valley and onward to Manchester. How many people however, know of the existence of an even longer (although rather smaller) tunnel situated some four and a half miles to the north? This 4.5 mile long tunnel was built to carry Sheffield's share of the water from the Derwent Valley Impounding Scheme, a job that it still does today after almost a hundred years. During the construction enormous quantities of water were encountered and even today about 5% more water exits the tunnel than enters it. .

Rivelin Dams - Wikipedia

The Rivelin Tunnel - Sheffield History Chat - Sheffield ...

Way: Rivelin Tunnel (203907300) | OpenStreetMap

87

Sheffield Water Works - A Collection of Items Relating to Mr William Terrey, Assistant, Later

THE RIVELIN TUNNEL, 1903-1910

JEAN CASS

INTRODUCTION

On the sixth of October 1909 the general manager of the Sheffield Corporation Waterworks department, Mr. W. Terrey, presented a report [1] to his committee which was subsequently heard and minuted by the City Council. The report summarised the labours of just over six years spent tunnelling through hard shale and millstone grit in order to convey the headwaters of the Derbyshire Derwent into the Sheffield water mains at Rivelin.

First he described the structure of the tunnel, then emphasised the historical importance of the work. The arched tunnel was four miles 612 yards long, six feet six inches high, and six feet wide, with a `dished invert' [2]at base hollowed out to facilitate the free flow of water. The walls were lined with brick or cement concrete as and where necessary.

The two headings - one driven from Rivelin (Fig. 1) the other from near Ladybower - had met on 20 September, 1909, "the levels agreeing at the point of junction within half an inch." [3]

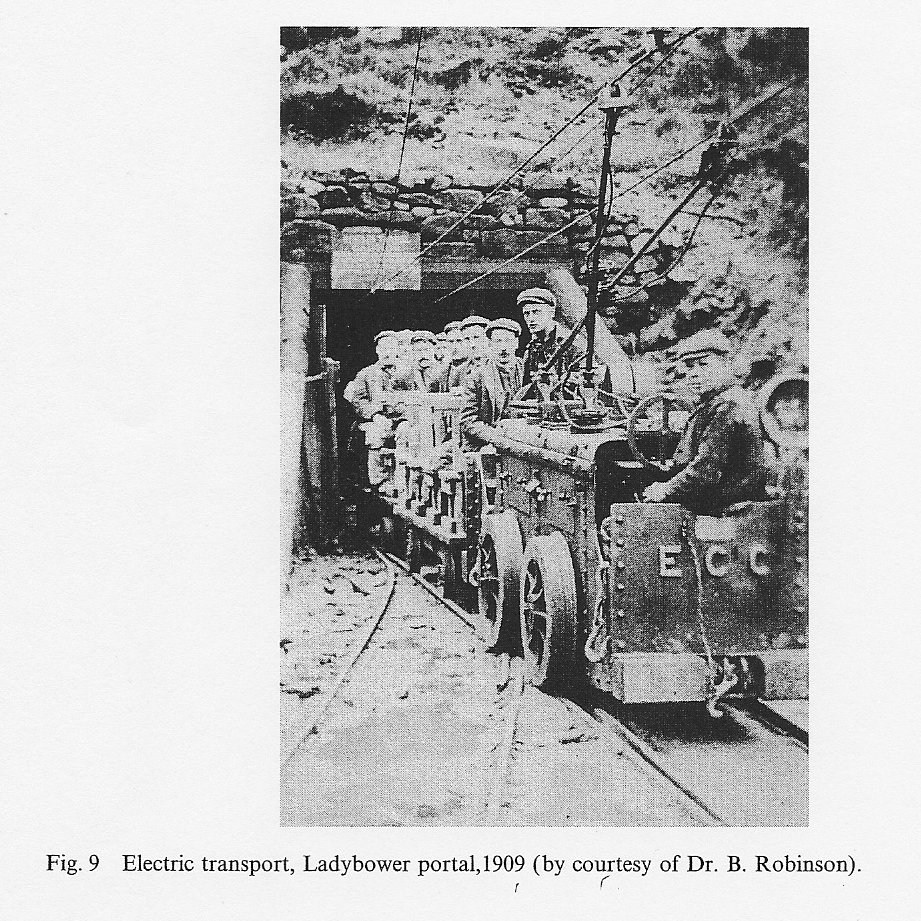

The tunnel had been driven without shafts, but even more remarkable was the fact that the `whole of the apparatus for driving, pumping, ventilation and lighting had been worked by electrical plant which greatly conduced to the health and comfort of the workmen and to the efficient and economical working' [4];by comparison with the normal use of contractors' plant and horse haulage.

At the time public attention was focussed on the two large reservoirs under construction at Howden and Derwent, in the Derwent valley, and not on the Rivelin tunnel. The design and construction of the works was the responsibility of the Derwent Valley Water Board.

Sheffield and other Midland towns had submitted separate Bills to Parliament with the object of acquiring the resources of the Derwent, but the Chairman of the Select Committee had insisted on one joint plan, hence the Act of 1899 creating the Board.

The constitution had been carefully framed, but the maps and plans were a hurried, unworkable amalgamation. The Act did make it clear that Sheffield would be responsible for conveying its allocated share from the Derwent reservoir to the city's existing water supply.

A private water company had driven tunnels under the Crookes and Stannington ridges in the nineteenth century, but little is known of their construction. However, for the Rivelin tunnel, there now exist in Sheffield sufficient available records to justify an investigation into the great work.[5] There are also structural remains which must be recorded before they become an archaeological mystery.

It is regretted that the writer is not a surveyor; but for those who would like to explore Grid locations are given in the References. Any alternative suggestions regarding the mysterious hut will be welcome; nobody survives who once walked on the erstwhile private land.

Preliminary Activity

In 1898 the Water Department of Sheffield City Council had only been in existence for ten years, following the purchase of the private company. The pressure of demand and competition from neighbouring authorities had committed the city to the construction of two large reservoirs in the upper Don valley, currently in hand. No other major works were contemplated. But in the spring of 1898 the Water Committee decided that `in view of enquiries now being made in Derbyshire on the subject of the public water supply[6] the Town Clerk should make `friendly connections [7] with the Derbyshire authorities respecting the long subsisting claim of Sheffield to a portion of the ... resources of the rivers Derwent and Ashop.'[8]

The claim rested on the tributaries of the upper Derwent - within the statutory area of supply - and the flow by gravity of any extracted water towards Sheffield. The Corporation had no intention of emulating other cities by going far afield for supplies; here were gathering grounds only twelve miles away.

Throughout the summer of 1898 the local officials laboured, without success, to persuade Leicester, Nottingham and Derby to become partners in a joint scheme. Derby, whose surveyors had been particularly active, even refused to attend the conferences.

In September Alderman Gainsford, the forceful chairman of Sheffield Water committee, was warned by an adviser that if Sheffield decided to `go it alone there would be a fair stand up fight with Derby'.[9] However the enforced compromise was enacted.

The Board first met in November 1899, Gainsford was elected chairman and plans were formulated for a professional survey of the gathering grounds. Mr. E. Sandeman M.LC.E. was appointed and he made suggestions which were greatly to the benefit of Sheffield.

The proposals were approved and formulated in 1901 into a Bill amending the 1899 Act. The first two reservoirs to be built were to be the Howden and Derwent, the latter to be further upriver and to have a higher embankment. Thus, instead of Sheffield paying for a separate aqueduct from Derwent, the city could share in the joint aqueduct running south as far as a turnoff point between Ashopton and Bamford.

As the revised line of the joint aqueduct would, at the turnoff point, be running at 700 ft (210 m) Sheffield would be able to take water, flowing by gravity, to the Hadfield service reservoir at Crookes. This supply would increase the middle zone water resources, relieving the demand from the highest reservoirs at Redmires.

The Board confirmed the alterations in their Act of 1901, leaving Sheffield to make statutory provisions for the new alignment of the tunnel and the point of exit. Preparatory agreements for access and easements had already been started by the Town Clerk; the alterations to the line of the tunnel and the position of the entrance (made to accommodate the landowners concerned) could be included in the Corporation Bill planned for 1903.

The date caused some concern. Under the new arrangements work would start on the tunnel before the Royal Assent was granted. A long letter from the Town Clerk was dispatched to the city's counsel, Mr. Balfour Browne: would we be acting without statutory authority, in a manner disrespectful to Parliament, or could we prudently commence work? In the margin is a pencilled 'Yes.' [10]

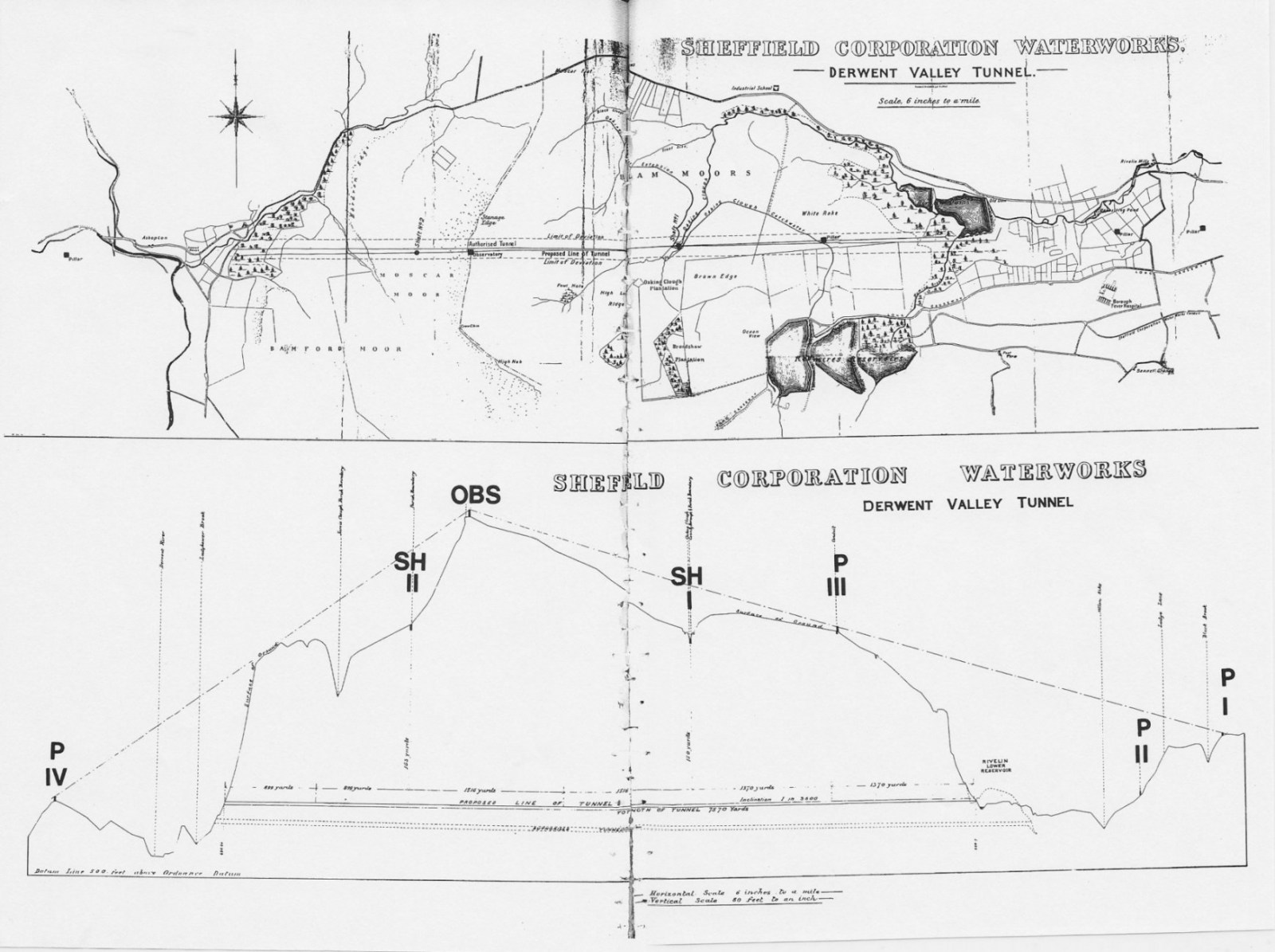

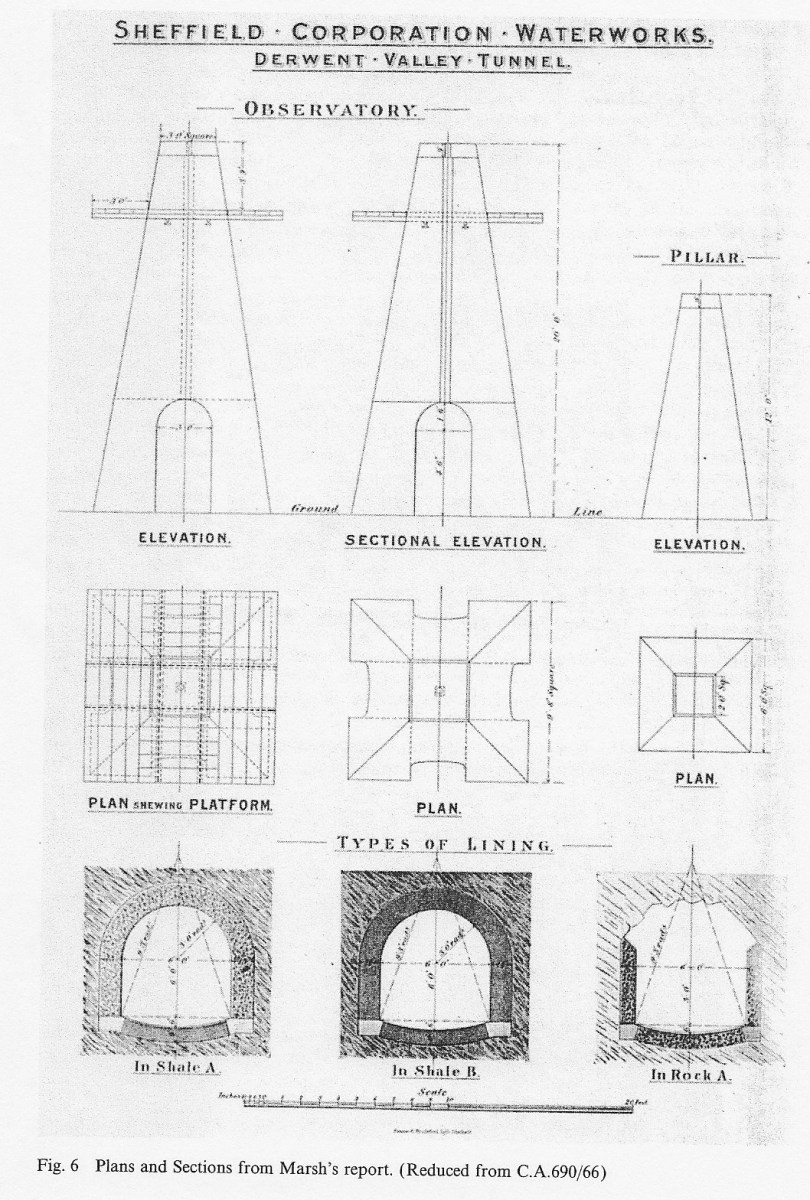

Meanwhile work had begun at Howden in 1901, and at Derwent a year later. In October 1901 the Sheffield water engineer, Mr. L. S. M. Marsh, was asked to prepare a report on the cost and organisation necessary for driving the tunnel. The report, with map, plans and sections, was submitted to the Water committee in January 1902, then forwarded to the Council.[11]

The precision of the map suggests that Marsh had had a team of surveyors working through the winter months. The map and section show the old and new lines of the tunnel and the sites of two possible shafts. These were the greatest problem. The cost of `power and tackle to lift against a head of 500 feet' [12] would add about £21,000 to the sum of £106,800 (the estimated cost of driving and lining the tunnel) but did not include subsidiary expenses.

Marsh and his assistant W. Watts, the resident engineer on the Don valley site, recommended driving from both ends and draining any water outwards, with no shafts sunk. Ventilation would be `through the air pipe laid to work the power drills' [13]; haulage would be by ponies.

All the accommodation would be provided for the men on site; they would work an eight hour day for six days a week. Reports on other long tunnels were submitted, including the recently completed Totley railway tunnel and opinions were cited on the feasibility of driving and lining at the same time. In all it was estimated that the driving would take five years and the lining another two. It was not thought that the Lower Millstone and Yordale rocks would cause any special difficulties. Certainly no exploratory shafts are mentioned; the shafts on early Ordnance Survey maps must have been for coal or stone as they pre-date the tunnel.

The first priority was to confirm the centre line of the tunnel, as drawn, on the surface. At this point it is practicable to comment on the positions given on Marsh's map for the sighting pillars and the observatory.

Starting from the east, Pillar no.I Must have been placed on the rocky promontory above Blackbrook wood at Rivelin [14]; Pillar no.II was in an area now cleared, three fields west of Lodge Lane; both have gone.[15] Pillar no.II was important because it was aligned with the sighting block which faced and lined up with the tunnel portal. The low block can be seen at the far end of the enclosure which protects the tunnel exit at Wyming Brook.[16]

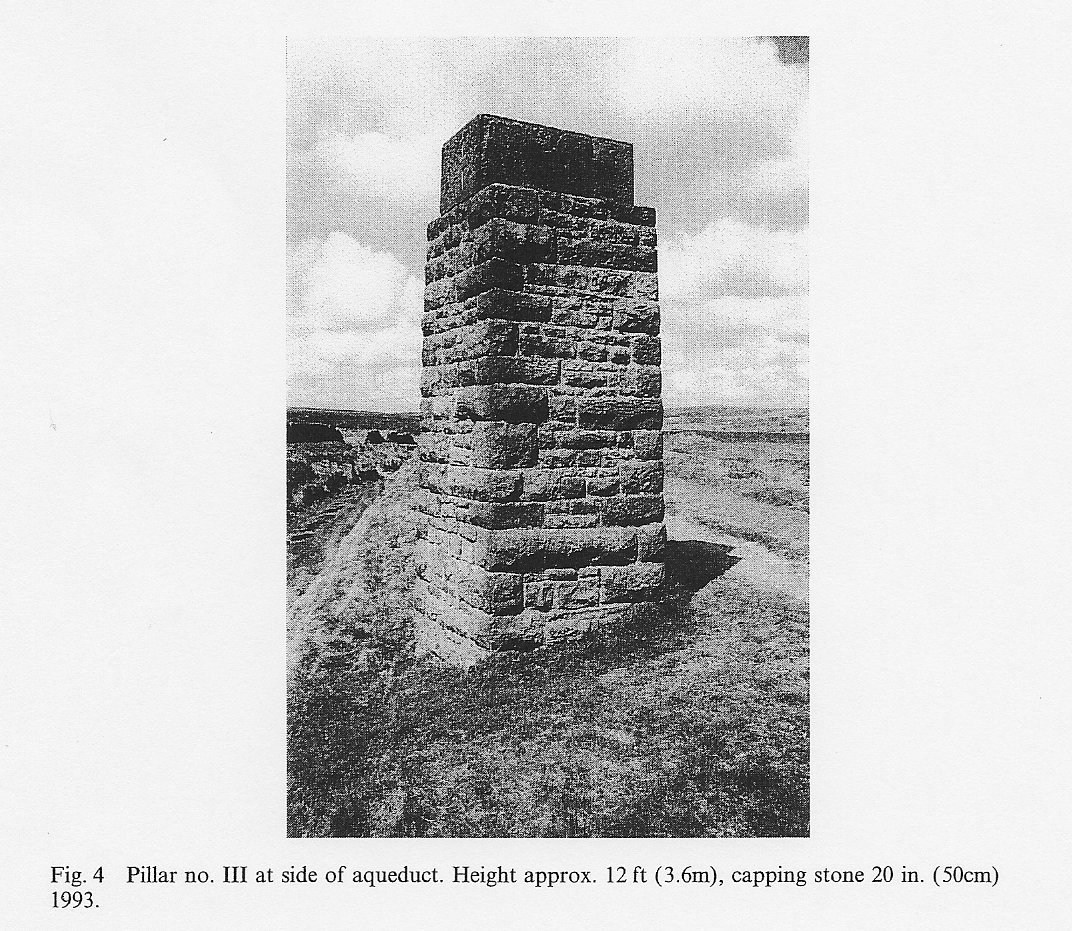

Pillar no.III stands firm and clear between the aqueduct to Redmires upper reservoir and a public footpath, but has never been indicated on Ordnance Survey maps. The capping stone has the remains of ironwork protruding; possibly it was a hook for attaching a ladder or a surveying instrument (Fig. 4). [17]

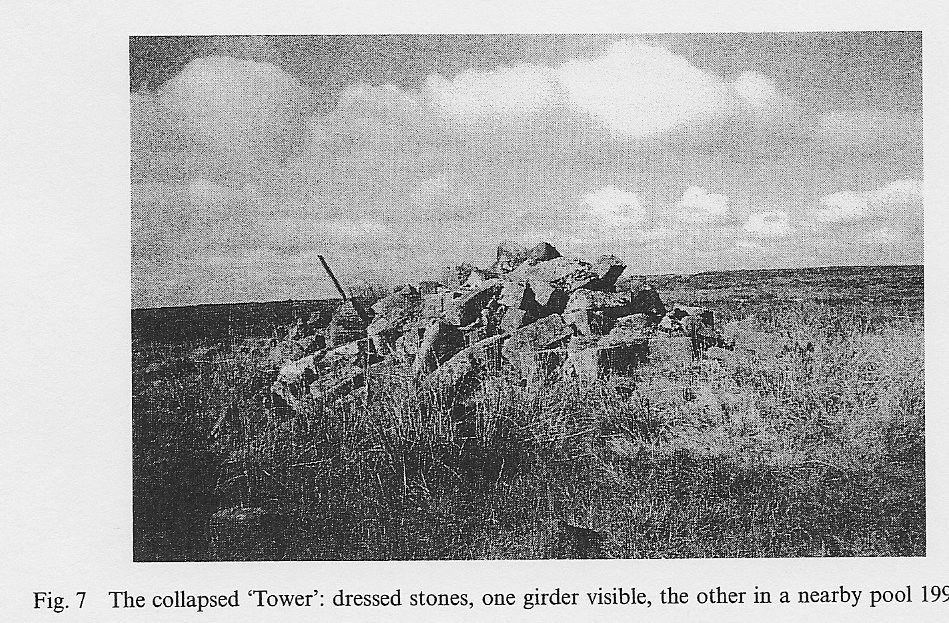

It is probable that the `Observatory' followed the plans drawn up by Marsh in 1902 (Fig. 6). Standing close to Stanage Edge, it was marked and named as a 'Tower' on maps between 1920 and 1960, but now only a heap of dressed stones and two girders remain (Fig. 7). [18]

From the top of the 20 ft high tower Pillars I, II and IV would have been visible on a clear day; even now, a short walk ENE. brings Pillar III into view.

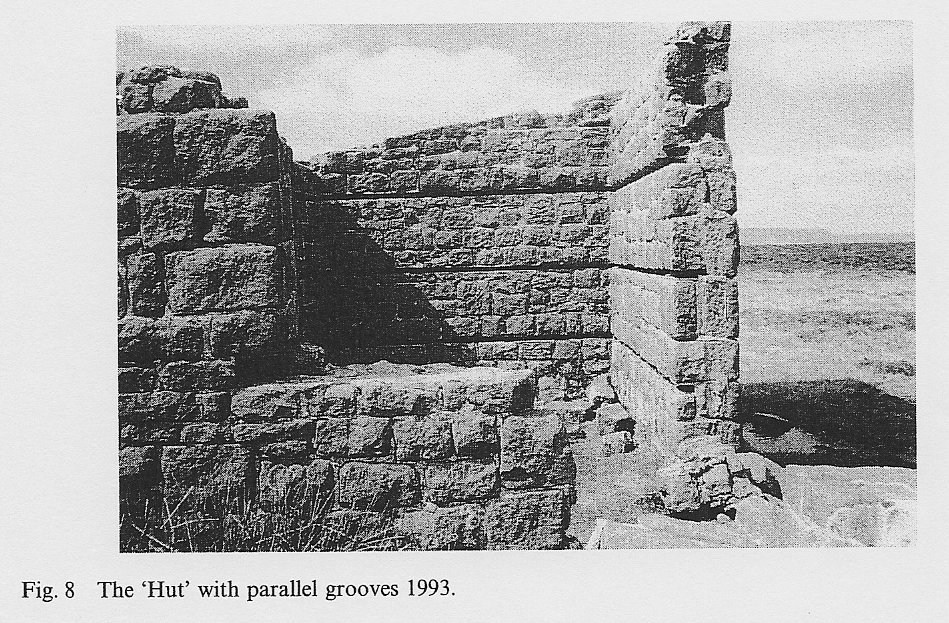

Nine yards south of the `Tower' is a roofless hut. Both tower and hut were superscribed on the personal map of the late local historian G. H. B. Ward.[19] The rectangular structure, of dressed stone, has interior measurements of approximately 9 by 8 ft.(2.7 by 2.4 m), with the back wall sloping upwards from 7 to 8 ft. (2.1 to 2.4 m) in height. The door and window apertures have collapsed, but the door faced the tower.

Inside, three parallel grooves run horizontally round the walls about 23 in. (58 cm) apart and 6 in (15 cm) deep; there are traces of wood within the 2½ in (6 cm.) gaps (Fig. 8). The grooves seem to be too near to ground and roof level to be for shelving but are part of the construction. Were wooden battens inserted for attaching equipment? There is a transit instrument in the keeping of the Faculty of Engineering of the University of Sheffield which is reputed to have been used in the surveying (see LD1752 p501 Plant Account); was it kept in the hut?

Hollow observatories were built for the Totley tunnel (1894) and had been built for railway tunnels in the south of England by 1844. [20]

One of the Totley engineers became the first resident engineer of the Rivelin Tunnel. Did he build a `Tower' as instructed and then a second tower for signalling and shelter? Any suggestions or solutions will be welcome. The `Hut' should be preserved.

The final Pillar, No.IV, for backsighting, was placed well beyond the tunnel entrance in the grounds of Ashop farm, now demolished. It probably stood below the site of the buildings on what is now the bank of the Ladybower reservoir [21] at a point where two further pillars, not on the Marsh 1902 map, can be seen. The construction and the position of these pillars, above Priddock House, suggests that they were built by the Board as extra sighting points. [22] They are the only pillars now marked on Ordnance Survey maps.

During 1902 and 1903, alterations in the land purchases were confirmed. Access to the observatory site was agreed using part of an old track from the Moscar road. This is now a popular footpath from which marker stones showing the initials of the owners, Wilson Mappin and William Wilson, can be seen (Fig. 5).

There are eleven neatly-dressed stones, measuring up to 27 in (68 cm) above ground and 10 in (25 cm) thick. Wilson was the owner of the observatory site; a draft agreement handed the building over to him once the tunnel was completed and he had also agreed to a possible shaft near Oaking Clough.[23] The terms of the Bill were proved by Marsh who clearly defined the new, higher, exit point of the tunnel `above instead of below the Rivelin Lower Reservoir'.[24] The official maps confirm this [25]; the description in the 1903 Act is faulty.

Preparations for Construction

The Committee put out tenders for the construction of the tunnel, but the possibility of a shaft being required deterred some contractors from submitting quotations.

It was decided to proceed by administration and advertise for a resident engineer experienced in tunnelling; he was to live at Priddock house, near the tunnel entrance. Marsh was appointed consulting engineer.

From the six applicants interviewed Joel Lean, M.I.C.E was appointed in February 1903, to commence work on the first of March. His obituary a year later described him as a man 'who worked on the most modern lines, introducing electric traction into the tunnel'; one of his most notable works had been the construction of the Totley railway tunnel. [26]

Subsequent events proved that he was a man capable of carrying his convictions into action. On the 18th of February Lean reported to the Water Committee. He had already walked the line of the tunnel (still a difficult route) and now requested authority to purchase a theodolite with a thirty-inch telescope to set it out.

The Committee suggested a secondhand appliance; Lean complied but subsequent repairs and renewals proved the falsity of the economy. He was also given permission to visit makers of machinery, for the air compressors and rock drills, and to enquire about methods of traction for removing the spoil.

It was important that the observatory and connecting pillars should be erected during favourable weather. Lean's proposals for driving the tunnel were submitted to the New Works sub-committee on the first of April. A copy was circulated to every member of the committee. Unfortunately the report has not been found but it was obviously revolutionary.

It was considered at a special meeting a week later, where tenders for the men's huts were approved and Lean was told to obtain quotations for electrical plant. A month later tenders were accepted from two firms to supply generating plant 'for obtaining the necessary power for driving the tunnel.' [27]

The boilers and fittings were ordered, the only delay occurring when one supplier withdrew. The first deposit on the plant was paid in November 1903.

There were to be no ponies for haulage, no shafts, and better ventilation for men labouring in a space only about 8 ft (2.4 m) across.

Work started before the royal assent to the enabling Act in August 1903. The Rivelin end was being excavated from 16th July and the Bamford end (as Ladybower was known) a week later. A weekly progress report for both ends has survived; this and the monthly purchasing lists provide much additional information. [28]

At first the men were working 'by hand' [29] through shale at Rivelin and through hard bands of rock and shale of the Yoredale series at Bamford.

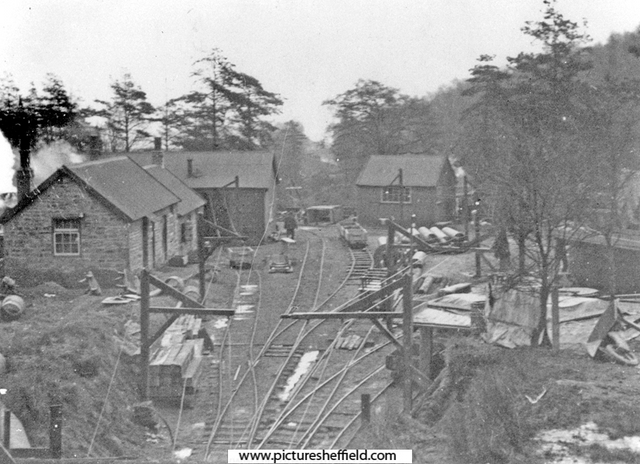

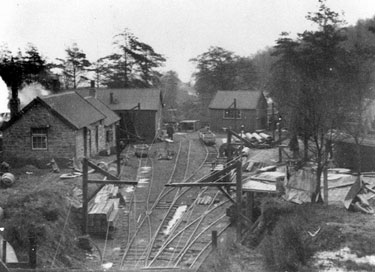

In October a portable engine was installed to drive the Rivelin fans. It was January 1904 before the generating plant was running at Bamford (Fig. 9); a month later at Rivelin the `power plant successfully started'. [30]

Had there been trouble? In March reserve machinery was bought in case the plant broke down, but such an event was never recorded.

Marsh had hoped to achieve an average of 15 yds (13.5 m) progress per week at each end. The Bamford end surpassed this rate for a time, once the electric plant was running. The rock was hard, little timbering was necessary, but blasting was difficult.

At Rivelin the ground became so heavy that extra timbering was required, and then in June 1904 an inrush of water held up progress.

By August, at the end of the first year, the Rivelin men had driven 717 yds (645 m), the Bamford men 743 yds (669 m).

All the accommodation was completed, an overhead trolley system was working and the Bamford supplies were coming up via the Board's railway serving the reservoir sites, then by aerial ropeway. Rivelin supplies came up by road, often by traction engine; from time to time the Highway authorities demanded payment towards the extra maintenance costs.

The monthly purchases authorised included: coal, tipping waggons, timber, candles, rock drills repaired, waterproof suits, a horse drawn ambulance and hand stretchers, and the installation of telephones.

The Committee decided to pay their first formal visit to the tunnel but, on the fourth of August 1904, Joel Lean died. It was said that he had never recovered from the pleurisy and pneumonia contracted through his work; certainly the Committee paid for his medical and funeral expenses.

Mr. Marsh was temporarily in charge, and almost immediately faced with deciding on the method to be adopted for lining the Rivelin end.

Driving had been stopped because 350,000 gallons (1.275 million litres) of water were coming in every 24 hours, but lining could proceed.

The Committee prevaricated; a mining expert was called in and recommended brick or cement concrete, as Marsh had proposed in 1902. Meanwhile Marsh was instructed to check the alignment of the tunnel. This process was repeated at intervals, and could only proceed when all the dust had settled.

Bricks for the lining were ordered and tested and the work began in February 1905, the timbering being removed with great care. At the Bamford end driving progressed at 20 yds (18 m) per week in November and December; but 'on 12 January 1905, considerable quantity of water met with, and driving had to be suspended.' [31]

The quantity decreased to 240,000 gallons (874,000 litres) per 24 hours but driving was deferred until July, after a deeper drain had been excavated. There was no driving at Rivelin until August 1905; lining had progressed but water was still coming in.

The new resident engineer, G. H. Carmichael, had been appointed in January. He had qualified since he had first applied for the post in 1903, but his first year was difficult.

The August 1905 figures were: Rivelin now 830 yds (747 m) driven 365 (329) lined; Bamford 1324 yds (1192 m) driven.

The expenses had been high; apart from the usual materials they had included: a new theodolite, electric motors to drive stone crushers, bricks, explosives, and, from now onwards, a regular fee for an electrical expert to check the appliances.

In the autumn of 1905 the Committee, having regard to the slow progress and mounting costs `gave certain instructions... there to' [32] regarding the engineering management.

As the Langsett reservoir on the Don was now operational it was possible to place Watts in charge of the Rivelin tunnel, with Carmichael as his deputy. Marsh was given responsibility for planning the distribution of the Derwent water into the Sheffield mains.

The Rivelin workers achieved a driving average of just over 15 yds (13.5 m) per week for the winter months, and continued with the lining.

At Bamford concrete lining began in December, somewhat impeded by the obstruction of an air pipe and the electric cable. Then in February snow and frost created conditions `quite unsuitable for mixing concrete'. [33]

Incoming water at the working face arrested driving; there were also labour problems. Piecework rates were negotiated and further adjusted in recognition of the difficulty of driving through rock that was `very close and massive with few joints' [34] and so bad to blast.

In the spring of 1906 Watts proposed an alteration which improved the transport arrangements at Rivelin. A depot, established on the north side of Manchester road (opposite the road over the embankment), could receive materials' coming up by road. At the depot equipment needed at the work face could be transferred on to waggons running along an extension of the line from the tunnel.

Spoil brought out could be conveniently dumped on the reservoir embankment, thus strengthening the wall. Watts anticipated no difficulty in obtaining permission to run the rail track across the highway (the present A 57).

The summer was spent in concrete lining; driving was in abeyance for four months. The Bamford men were still having problems with water; a second pump was put down, and a small amount of marsh gas was detected.

However, the August figures were better: at Rivelin 1383 yds (1245m) now driven, 1193 (1074) lined; at the Bamford end 1862 yds (1676m) driven, 669 (602) lined.

The year 1906-7 was a good one for Rivelin, driving often exceeding the average, except in October when it was necessary to use hand drills because the brickwork lining impeded the air compressor.

At Bamford driving and concrete lining proceeded, although sometimes the timber was left in to support the `considerable topweight' until the concrete had set. [35]

In February 1907 the draft Committee minutes contain a report from Carmichael not repeated elsewhere: there had been a roof fall at the Bamford end, seven men had been entombed but rescued safely and only three yds (2.7 m) of tunnel were affected.

An extra shift on Saturday nights was instigated for the men, at both ends, in May 1907. A month later Marsh presented his proposals for distributing the Derwent supply.

The costs were skilfully spread; first the 24 in (60cm) main to carry the water from the outlet basin to the Hadfield service reservoir at Crookes; then other service reservoirs at Ranmoor, Ringinglow and Lydgate to be improved to hold more Redmires water, thus keeping the Derwent waters for the middle zone of the city and relieving the demands on the high-level Redmires supply. Filtering the Derwent water was `left over'. [36]

Watts resigned in July 1907, giving a memorable speech: `to leave good work behind me has been my daily effort. [37]

Carmichael shortly afterwards received an increase of £50 on his salary of £400 p.a. and was left in charge.

In August the Rivelin men were lagging behind in the distance achieved; they had reached 2083 yds (1875 m) driven, 1568 (1411) lined; but at the Bamford end 2231 yds (2008 m) were now driven and 1797 yds (1617 m) lined. By November 1907 the Bamford men were about 774 ft (232 m) underground; the observatory being above them on Stanage Edge. The Rivelin men were a mere 500 ft (150 m) underground and between them stretched 2888 yds (2599 m) to be tunnelled.

A pencilled endorsement on a map and section describes the Rivelin workface as having `no water' [38]

However, at Bamford the engineers noted conditions which were 'unfavourable ...very variable... Kinder Scout grit close and massive.' [39]

Then in April 1908 the air compressor and locomotive broke down. This was followed by loose shale which required timbering, and in August an inrush of water from an open joint in the roof.

In spite of problems the August figures were the best achieved: at Rivelin 2877 yds (2589 m) now driven, 2658 (2392) lined; at Bamford 3079 (2781) driven, 2522 (2270) lined.

The most important purchase was the pipes for the Hadfield main,

delivered by motor lorry; also large quantities of `castings', not described but costly.

If the men had been taking bets on progress it seemed likely that the Bamford workers would win. At Rivelin the next year was uneventful, reaching a weekly peak in July 1909 of an average of 25 yds (22.5 m) driven and 20 yds (18 m) lined.

At Bamford there was the usual complaint about the Rivelin grit, always difficult to blast. On the 6th of April fate struck: an inrush of water which `gradually filled the heading from the face to within 260 yards [234 m] of the open end'. [41] Work was stopped; the drain was inadequate and until it had been relaid the three pumps could not start work. When the fourth, innermost, pump was reached the motor was removed and thoroughly dried out.

Late in June the face was reached and, in spite of water still coming in under pressure, driving was resumed on 5 July. Once the site of the influx was passed progress improved, with the pumps discharging water at a rate of about 550,000 gallons (2 m litres) per day.

The August 1909 figures reflect the reversal in fortunes; Rivelin now 3785 yds (3407 m) driven, 3498 (3148) lined, but at Bamford 3756 (3380) driven, 3066 (2759) lined. The two ends met on 20 September 1909, the junction being `in every respect satisfactory'. [42]

The Rivelin face had finished at 3868 yds (3481m), the Bamford face at 3784 yds (3406 m). An annotated map and section mark the meeting place. [43]

By the end of the year the invert - designed to run at an inclination of 1 in 3600 towards Rivelin - was under construction and the electricity supply was connected up and running from the Bamford end. The lining was completed by the following August.

There was no longer any urgency, as the Derwent Valley Water Board had discovered geological problems near the reservoirs, and wing trenches would be required to make the embankments watertight.

In Sheffield work continued throughout 1910 on the Hadfield main. Alderman Gainsford died in July; he had seen his work nearly completed. Later in the year Marsh and Carmichael walked right through the tunnel and found it `in thoroughly good condition'. [44]

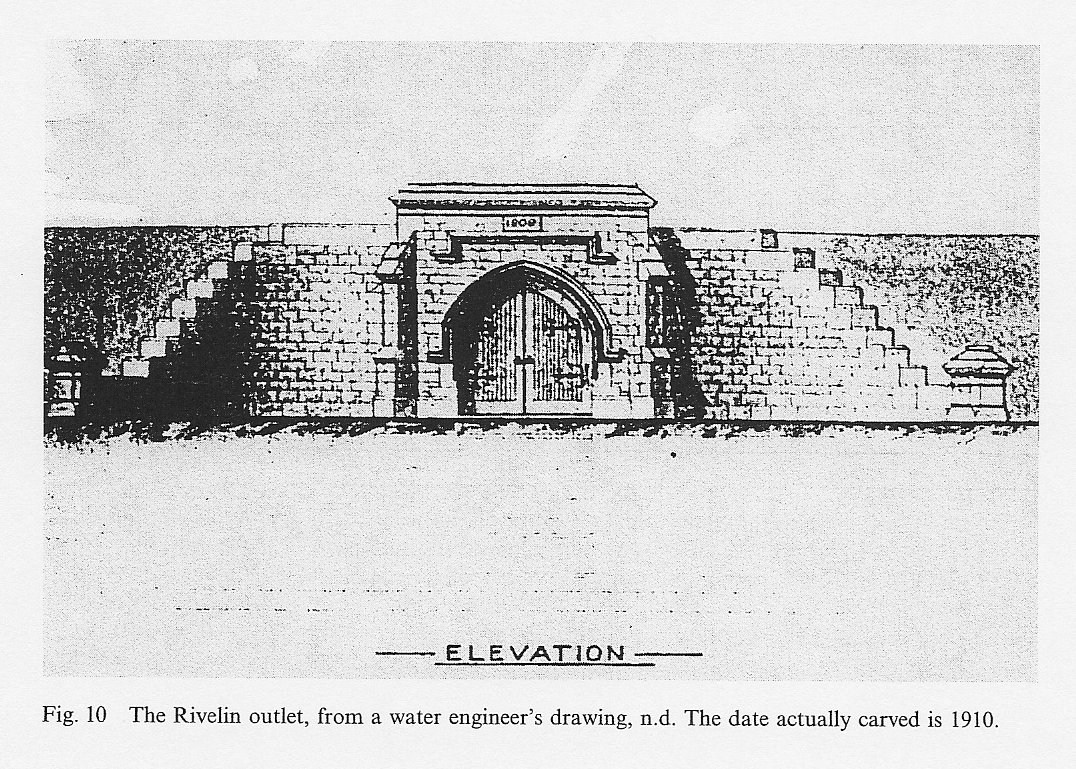

Carmichael left with the Committee recording their appreciation of his energy, and ability. His last work had been the supervision of the erection of the imposing stone exit arch and gateway at Rivelin. (Fig. 10)

In March 1912 Mr. Terrey, as General Manager, produced his final report on the tunnel. The total expenditure had been less than the lowest tender - £135,151 against £142,664 (with an additional £5,175 for the cost of supervision).

He referred also to the `difficulties of an exceptional character ... which could not have been anticipated' [45] and which would inevitably have increased the final expense.

The use of electric power had, by removing the need for a shaft, saved the expense of compensation to landowners for any interference with their game preserves.

Early in 1912 the Board completed the junction, at Ladybower, of their main aqueduct and the Rivelin tunnel; in the same year the Hadfield pipeline with its supplementary branches was finished.

At the grand opening ceremony on 5 September 1912 Howden waters were diverted into the joint aqueduct flowing south. [46]

On 8 March 1913 the first instalment of a daily supply of two and a half million gallons flowed through the tunnel and the Hadfield mains into Sheffield. This quantity has increased as further works have been completed. It was considered that the water would be pure, but obviously peaty; shortly after the first delivery pressure filters were completed at Rivelin to sift out the peaty deposits.

CONCLUSION

The tunnel is still in use; the steady rush of water is audible where it flows over the final weir, just inside the exit portal at Wyming Brook. The water now runs into the Rivelin Lower reservoir, where preliminary settlement of the peat eases the filtering and treatment processes undergone at the Rivelin waterworks.

In 1949 the tunnel underwent a thorough inspection, the men travelling by boat along a controlled flow of water. Apart from some seepage, and an accumulation of silt, the structure was in very good condition.

The records from which this account has been collated pay tribute to the efficiency of a Corporation department guided by a conscientious committee and an outstanding chairman, all prepared to serve the community to the best of their ability.

It is hoped that the visible structural features mentioned will be preserved as a witness of what lies underground, and as a stimulus to a more technical interpretation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My most sincere thanks must be expressed to the staff of Sheffield City Libraries and Sheffield City Archives for their endless patience and interest during my researches, and to the Director of Libraries, Sheffield Libraries and Information Services for permission to reproduce maps and plans from Yorkshire Water manuscripts. I am most grateful for the expert advice and practical help given to me by Ms. J. Poole and other members of Yorkshire Water Services Ltd., and to Dr. B. Robinson for the copy of Fig. 9. Very many of my friends and relations have been coerced into checking sites and discussing maps; their support is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES.

1. CA 136/6

2. ibid

3. ibid

4. ibid

5. See Primary Sources

6. CA 136/3, 6th April 1898

7. ibid

8. ibid

9. CA 433/15. `The Genesis of the Scheme'

10. CA 433/16/31

11. CA 690/66

12. ibid

13. ibid

14. SK296867

15. SK288866

16. SK273866

17. SK262865

18. SK226862; and see Makepeace, G. A. 1987. An Archaeological Survey of Bamford and Hathersage Outseats, Derbyshire. Transactions of the Hunter Archaeological Society 14 53.

19. Map F10L, Local Studies Library. The note in `Clarion Rambler' 1962-3 p.59 is incorrect; the Derwent Valley Water Board had no forerunners.

20. Rickard, P pp. 118,119; Sowan, P. W. pp. 14,15.

21. SK189862

22. SK207860; SK209861.

23. CA 690/12; SK248863.

24. CA 608/34.

25. ACM 5551; see also YWA 2/89.

26. Sheffield Daily Independent 5 August 1904. 27. CA 136/4, 6 May 1903.

28. YWA 1/120; Water Committee minutes in Council minutes, Sheffield City Libraries.

29. YWA 1/120.

30. ibid.

31. ibid.

32. CA 136/5, 29 September 1905.

33. YWA 1/120.

34. ibid.

35. ibid.

36. CA 136/5, 5 June 1907

37. CA 136/5, 5 July 1907.

38. YWA 2/89.

39. YWA 1/120.

40. Water Committee minutes (see 28)

41. YWA 1/120.

42. CA 136/6, 6 October 1909; YWA 1/120.

43. YWA 2/89.

44. Water Committee minutes 9 November 1910.

45. CA 136/7, 6 March 1912.

46. Sheffield Daily Telegraph and Sheffield Independent, 6 September 1912.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A. Primary Sources

The manuscript sources consulted are in Sheffield City Archives (list below). Direct quotations have been individually referenced.

ACM 5551. Maps and Plans for Parliamentary session,1903.

CA 7/19 Letter book of W.Watts, water engineer, 1904-7.

CA 136 Minutes of Sheffield Waterworks Committee, 1898-1914, 1958. (see also Council Minutes).

CA 203 Draft minutes of above.

CA 433 The founding of the Derwent Valley Water Board.

CA 605 Sheffield Corporation Act 1901, papers.

CA 608. Sheffield Corporation Act 1903, papers.

CA 690 Town Clerk's papers on Derwent Valley Water Board

LD 1751,1752 Ledgers of the Board for the tunnel.

MD 3450,3451,3456 Alderman Styring's papers relating to water committee affairs YWA 1,2. Maps, plans and reports deposited by Yorkshire Water Services, Southern Division

Abbreviations: ACM Arundel Castle Manuscripts; CA City Archives; LD Loan Deposits; MD Miscellaneous Documents; YWA Yorkshire Water Authority.

B: Secondary Sources.

Acts of Parliament. The Derwent Valley Water Board, 1899, 1901, 1909. Sheffield Corporation Act 1903.

Beaver, P.1972. A History of Tunnels.

Bowtell, H. D. 1977. Reservoir Railways of Manchester and the Peak.

Burton, A. 1992. The Railway Builders.

Derwent Valley Water Board. 1912. History and Description.

Derwent Valley Water Board 1899-1913 Minutes.

Rickard, P. 1894 Tunnels on the Dore and Chinley Railway.Proc. of the Institute of Civil Engineers, CXVL, 115-175 (copy of article in Sheffield Local History Library)

Robinson, B. 1993. Walls across the Valley. Cromford.

Sheffield Corporation Waterworks. Annual Reports and Accounts, 1898-1914 (in YWA 2).

Sheffield City Council Water Committee. Minutes. (Local History Library copies include monthly purchases).

Sheffield Waterworks Committee. Handbooks. 1903, 1924, 1932, 1938, 1948, 1954, 1961

Sowan, P. W. 1993 Notes on the Bletchingley, Mersham and Quarry Line Tunnels' Observatories East Surrey. Industrial Heritage. 2,.14,15.

Terrey, W. 1908,1924. History and Description of the Sheffield Waterworks.

This addendum is reproduced by kind permission of the Hunter Archaeological Society

THE RIVELIN TUNNEL, ADDENDUM

By JEAN CASS

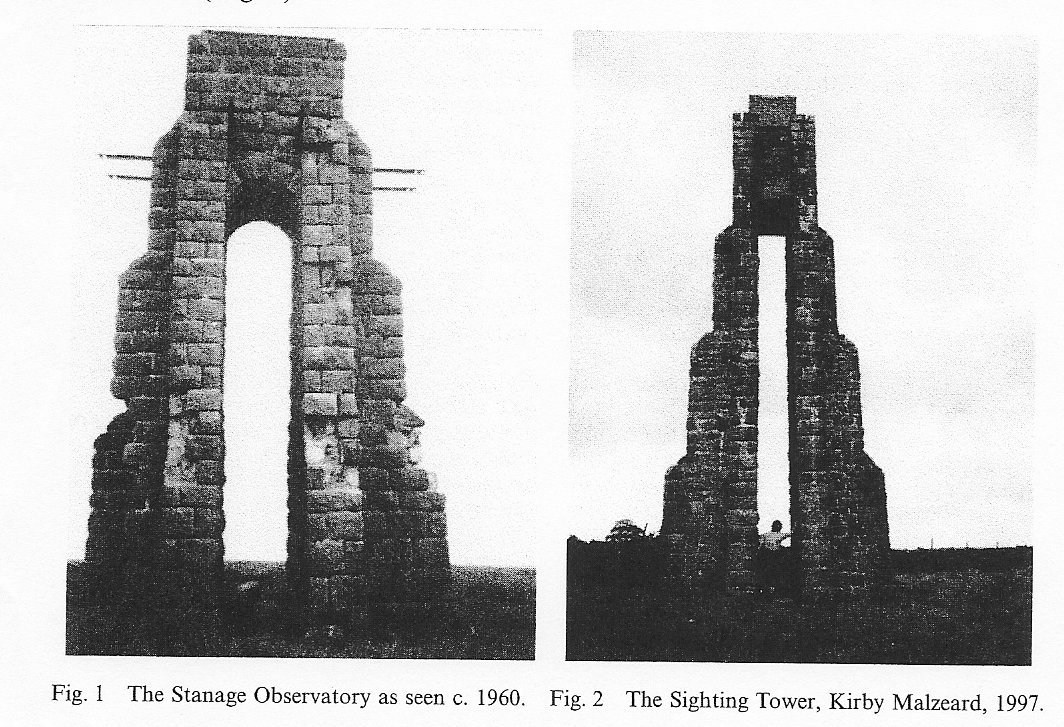

In `Transactions' volume 18 (Cass 1995), I reported on the driving of this tunnel and included references to the Sighting Tower (called an `Observatory') which was erected on Stanage Edge to determine the precise line of the tunnel (op cit., Fig. 6, p. 66).

Now, only a heap of stones remain at SK226862 (op cit., Fig. 7, p. 67) but, fortunately, a member of the Society remembered taking photographs of the site when he was making an archaeological survey of the area some years ago (Makepeace 1987). He has provided visual evidence with a photograph dating from about 1960 .(Fig.1)

A further confirmation has recently come to light. On the Ordnance Survey Landranger map of the Northallerton area (Sheet 99) a `Sighting Tower' is marked, to the east of Kirby Malzeard (SE196738). This tower still stands (Fig. 2).

It was built to assist surveyors planning the route of a tunnel designed to convey water from Roundhill reservoir to Harrogate, and is of a similar, probably standard, design, although at least ten years later. The tower is hollow, having archways set into the four sides. It has been suggested that scaffolding provided access to the top, but it is not clear how the transit instrument would have been secured.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I must express my sincere thanks to Mr. Makepeace for his contribution and to the staff of the Pateley Bridge Museum and other local experts for their assistance.

REFERENCES

Cass, J. F. The Rivelin Tunnel 1903-1410 Transactions HAS, 18, 60-74

Makepeace, J. A. 1987. An archaeological survey of Bamford and Hathersage Outseats, Derbyshire Transactions HAS, 14, 43-55

Following Jean Cass's excellent history of the Rivelin Tunnel, published here in August 2010, hildweller posted a comment and a photo of the tunnel exit. His last two sentences referred to the tunnel’s entrance, somewhere in the wood behind the Ladybower Fisheries Office.He wrote “Has anyone ever seen this portal I wonder. I’m afraid exploring up there is beyond me nowadays.”

Please see the attached photo, taken from the woods behind the Fisheries. I was surprised to find that the Rivelin junction is open to the elements, outside the Valve House. The flow from right to left is the gravity fed flow from Derwent to Bamford filters. The flow towards the bottom right of the photo is Sheffield’s supply, about to enter the Rivelin Tunnel.

Totley Grange

Totley History Group - Totley Rise Walk

Totley Grange was a manor house near Totley's Cross Sythes pub. It was built in 1875 by Ebenezer Hall. He had bought the land from Mr. Parker who had bought it from George B. Greaves. Thomas Earnshaw, a fish and game dealer lived in the house around the 1890s which gave the house the nickname of Fish Villa. During the 1939 to 1945 war, some kind of electrical wiring work was carried out in The Grange by local women. In 1965, work begun on the construction of Totley Grange Estate. Workmen found well lining stones which from the findings could have held water sufficient to feed flora from large greenhouses and gardens.

Sixty-five houses now lie on the estate of the former house.

Thomas Earnshaw and Totley Grange

by Richard Maw

The first Thomas Earnshaw was born in 1816 in Dronfield, Derbyshire. An indenture dated 22 June 1829 between his father John Earnshaw and James Green, pen-knife grinder of Sheffield, witnessed his apprenticeship as a pen-knife grinder for a period of seven years. By 1840 he was living in Club Gardens, Sheffield and in that year his third child also called Thomas (the second) was born. In 1861 the family was living at the Ball Tavern, Carver Street, Sheffield and ten years later was at the Crown Inn, London Road, Sheffield. The second Thomas married Hannah Copley in 1861 and by 1871 the couple were living at 69 Broomhall Street. Thomas was then listed as a Fish and Game dealer.

Land at Totley

An indenture dated 2 April 1875 confirmed absolute sale by Thomas

Andrews to Thomas Earnshaw of land and hereditaments at Totley measuring

2 acres, three roods (1 rood = quarter of an acre) and 14

1/2 perches (1 perch = approximately 30 and a quarter square yards)

bounded to the north and east by land of Ebenezer Hall and to the south

by the Baslow to Sheffield turnpike road (heretofore the

land had been two pieces, Cawston Croft and Yew Croft); and on 31

December 1875 the freehold was conveyed to Thomas Earnshaw at a cost of

£946 17 shillings and sixpence. There is another conveyance

between Ebenezer Hall to Thomas Earnshaw of the freehold ground,

buildings and hereditaments at Totley, dated 27 March 1878, of 3 acres

and nine perches which included Moorview House and six cottages

of Shrewsbury Terrace at a cost of £2,428. The land abutted Thomas

Earnshaw’s previous purchase to the south. To the north and east was the

land of Mr Ebenezer Hall.

On 26 March 1879, from Helen and Charles Beckett, Thomas Earnshaw purchased land of 1 acre together with a dwelling house and the terrace of houses facing the turnpike road and the Cross Scythes public house for £600, marked 174 on a plan referred to by Fowler and sons, Sheffield on September 21, 1879 (see picture below). Additionally from John Howard, Thomas purchased the land to the east of the one acre (marked 176 on the same plan) also facing the turnpike road, of 4 acres, 2 roods and 35 perches for £1500. Subsequently the house on the one-acre plot was demolished.

Totley Grange

Between 1883 and 1888 Thomas Earnshaw built Totley Grange and its Lodge

on the land he had purchased north of the Baslow to Sheffield turnpike

road. He also built stables, a stable yard and a coach

house accessed via Butts Hill past Cannon Hall Farm, together with a

range of glasshouses within the walled garden. Later he built Grange

Terrace; which was a row of eight houses, to the east of the

existing Terrace on the one-acre plot, facing the turnpike road.

On 1 June 1885 the Sheffield Telegraph quoted “prize hothouse grapes grown by Mr Earnshaw of Totley Grange are now ready for cutting”. On 31 July 1890 the Telegraph quoted “Totley Grange gives its name to a variety of tomato”.

By 1881 Thomas and Hannah Earnshaw had moved to 89-91 Broomhall Street, Sheffield. Their children were Thomas (the third) born in 1865, Arthur in 1871, Hannah in 1875 and Bertha in 1881. Finally, Anne was born in 1884. In the 1891 census they were still living in Sheffield, But Thomas’s father (the first), aged 75 was living in Totley Grange Lodge. Thomas (the second) and Hannah’s eldest daughter, also Hannah, aged 16 was living with her aunt, Sarah Copley in their newly built Totley Grange, pictured below.

1892 saw many purchases by Thomas of different varieties of orchids, lilies and camellias for the glasshouses. Also in 1892 Thomas Earnshaw purchased three cottages in Butts Hill, Totley from George Boot for £260. One of these was known as Greens cottage (later, in 1989 a new house also called Greens Cottage was built on the site).

Thomas Earnshaw made very regular visits to the Grange from Sheffield; and on one of these, when checking the gardens, he was caught in the rain and developed a cold which progressed to pneumonia. He died on 3 May 1893 aged 58. The Evening Telegraph and Star of 5 May reported his funeral cortege leaving Broomhall Street for interment in Ecclesall churchyard. His obituary was recorded in the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent of 4 May 1893. It quotes “in 1875 such had been his success that he built an handsome residence in Totley, known as Totley Grange. Strange to say he only slept there once…”.

In addition to his freehold land and buildings in Totley he also owned freehold land and 59 houses or cottages in Sheffield with 28 other leasehold houses or shops.

The family continued to live in Totley Grange. Hannah Earnshaw, now widowed, with her children and their maternal aunt Sarah Copley. Their elder son Thomas (the third) took over the family fish and game business in Broomhall Street, Sheffield. The second son, Arthur, qualified as a Doctor of Medicine at Guys Hospital, London. The elder daughter, Hannah, married and moved to live in Vienna. Bertha continued to live in the Grange, was married and later moved to Baslow. Anne married and lived in Sheffield before moving to live in Moorview House, Totley. Their mother Hannah died in 1937.

In 1943 Totley Grange was used for essential war work by J.G. Graves, assembling wire bundles for a range of World War Two aircraft, and in 1948 the trustees of the Thomas Earnshaw (senior) trust converted Totley Grange into five flats.

On 6th of March 1953 the trustees signed a deed of exchange with the Lord Mayor, Aldermen and citizens of Sheffield for the compulsory purchase of the land in Totley to the south of the turnpike road for £444.10 shillings. This was the land purchased by Thomas Earnshaw in 1879 for £1500. It is now the site of Totley Primary School.

In 1965, Totley Grange, the Lodge, all of the outbuildings and gardens and approximately 6 acres were purchased by George Wimpey. The buildings were demolished and it now comprises 65 houses as the Totley Grange estate. Subsequently the houses in Grange and Shrewsbury Terraces and Moorview House have been sold, and finally the remaining one-acre plot behind Grange Terrace was sold.

Richard Maw (Great-grandson of the second Thomas Earnshaw) December 2019

No comments:

Post a Comment